05 Design a DRIVEN Brand

DRIVEN humans don’t need more options—they need structure. Learn how to engineer a high-performance lifestyle, personal brand, and business ecosystem built to regulate dopamine, reinforce identity, and turn relentless pursuit into sustained momentum.

Introduction

The DRIVEN are wired differently. Standard routines and conventional paths often feel like cages, not frameworks. Their biology demands novelty, intensity, and relentless forward motion.

For this subset of high performers, dopamine isn’t a reward—it’s a fuel source. Without structure, they spin out. With precision, they dominate. This article offers a three-step framework: design a lifestyle that regulates your neurochemistry, build a personal brand anchored in truth, and launch a business built to sustain progress.

This isn’t self-help. It’s infrastructure. Crafting a lifestyle that resonates with intrinsic drive isn’t just beneficial—it’s imperative. This article outlines a strategic plan to design a lifestyle and brand that not only the neurological wiring of the DRIVEN but also amplifies their potential.

Step 01 | Design a High-Performance Lifestyle

Variants in the DRD2 and DRD4 dopamine receptor genes are associated with diminished dopamine sensitivity—a biological driver of novelty-seeking behavior, attentional shifts, and reward dysregulation¹. DRIVEN individuals need a system that delivers reliable, high-quality dopamine—without chaos. These traits demand a dopaminergic structure—a daily rhythm that delivers clean, consistent doses of earned dopamine through high-performance habits.

Unlike dopamine dumps (junk food, porn, social media), positive dopaminergic activities support long-term focus and mood stability, including:

Sunlight exposure to regulate circadian rhythm²

Red light therapy to stimulate mitochondrial activity³

Cold exposure and sauna cycling to trigger norepinephrine and dopamine release⁴

Fasted training and animal-based nutrition to optimize metabolic activity⁵

Deep work, creative sprints, and precision routines to stimulate meaningful reward circuits⁶

The DRIVEN aren’t designed to relax; they’re designed to pursue. But unmanaged pursuit leads to collapse. A high-performance lifestyle prevents burnout by managing the nervous system while delivering stimulation.

The result? Biological sustainability for long-term ambition.

Step 02 | Build a High-Performance Personal Brand

For DRIVEN founders, personal branding isn’t ego—it’s architecture. Your brand is how you structure identity, create consistency, and remain legible to the world.

Self-determination theory shows that identity, autonomy, and mastery are the three deepest human motivators⁷. Building a personal brand reinforces identity and autonomy—two critical levers for DRIVEN psychology.

But this brand can’t be a highlight reel. But the signal must match the source:

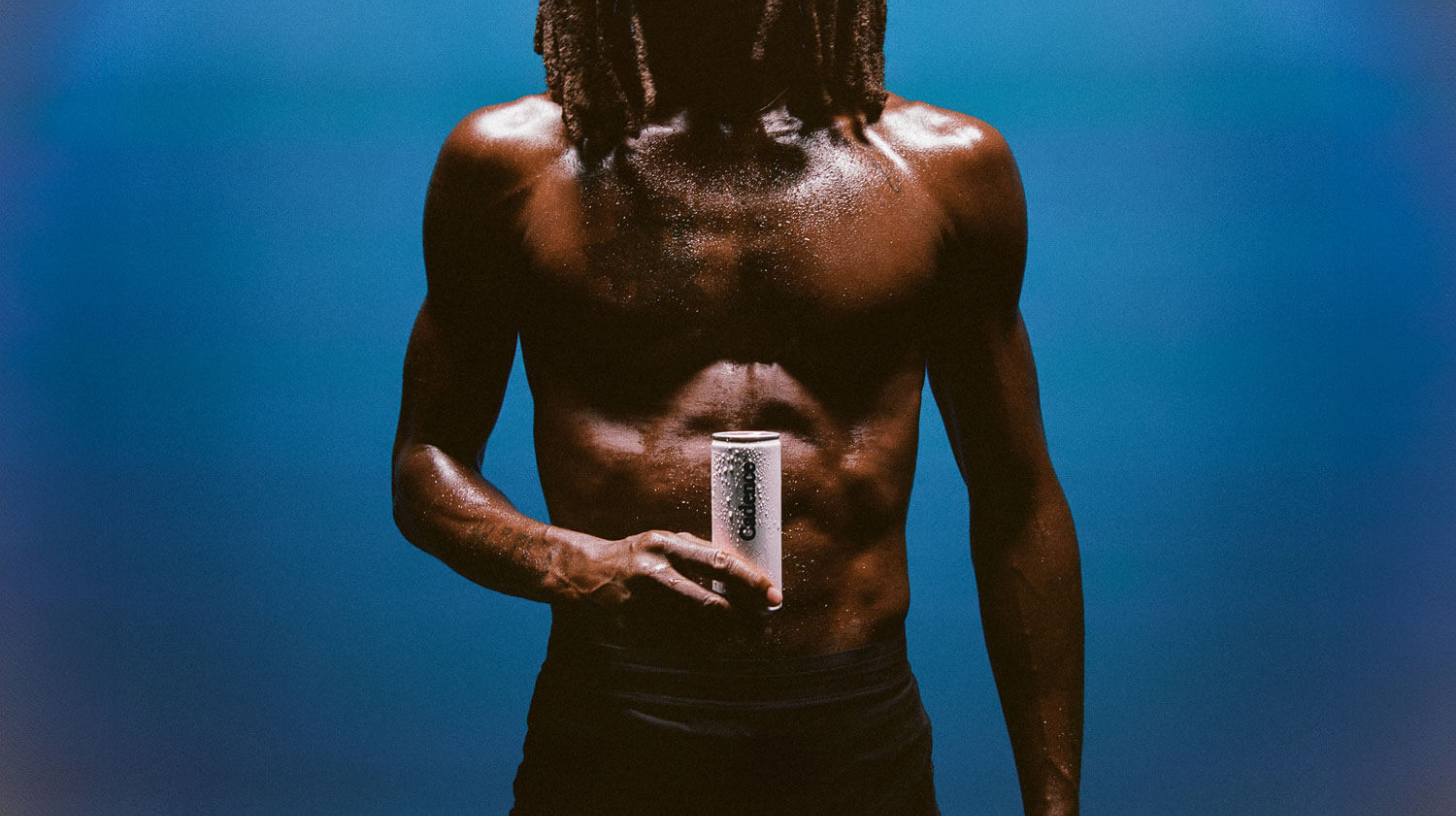

Rituals that reflect lifestyle (training, recovery, nutrition)

Visual design ethos that reflects structure (negative space, depth of field, monochrome color palettes)

Narrative arc documenting pursuit (obsession, resilience, hyper-focus)

This brand is built to resonate, not impress. When the DRIVEN founder designs a personal brand rooted in biological truth, it creates resonance—and attracts others wired the same way.

Your lifestyle becomes your message. Your habits become your magnet.

Step 03 | Launch a High-Performance Lifestyle Brand

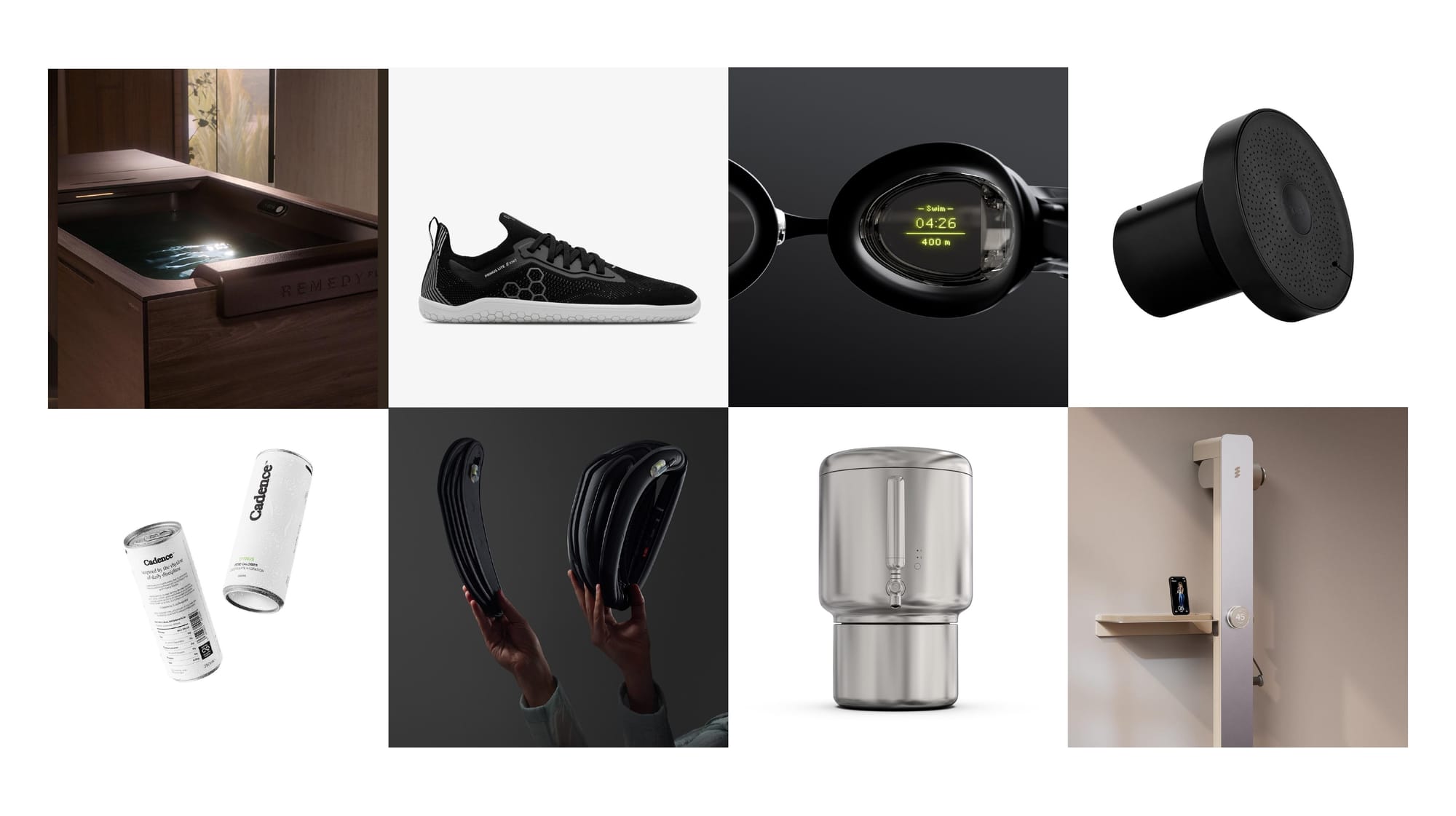

But the product or experience isn’t enough. The brand must do what DRIVEN humans biologically require:

Trigger healthy dopamine through sensory design, anticipation loops, and momentum cues that activate the brain’s reward systems without overstimulation⁸.

Minimize friction with simplicity over options, clarity over complexity, and structure over spontaneity—reducing executive load in brains wired for novelty but prone to distraction⁹.

Create ecosystems of progress—not just products, but programs, protocols, and pathways. The DRIVEN don’t just consume—they track, calibrate, and optimize.¹⁰

Research confirms that individuals with dopamine-sensing deficiencies (e.g., DRD2/DRD4 gene variants) struggle with executive function, sustained focus, and internal reward regulation.¹¹ They need visible feedback loops and rigid structure to engage their full potential.¹² In other words, DRIVEN brands must do what the DRIVEN brain cannot do on its own: regulate, reinforce, and reorient.

The best DRIVEN brands don’t sell things. They structure progress.¹³

Conclusion

For the DRIVEN, a structured lifestyle, enigmatic personal brand, and a boutique business engineered for continuous improvement aren’t “nice-to-haves.” They’re non-negotiables necessary to regulate dopamine, anchor identity, and sustain the pursuit.

This isn’t branding. It’s bioengineering. A DRIVEN lifestyle brand isn’t born from creativity alone—it’s forged through constraint. Design to hold tension, transmute chaos, and convert relentless ambition into a system that performs under pressure.

Because when structure and environmental align with biology, the DRIVEN don’t just succeed. They dominate.

References

- Blum, K., Noble, E. P., Sheridan, P. J., et al. (1990). Association of the A1 allele of the D2 dopamine receptor gene with severe alcoholism. JAMA, 263(15), 2055–2060.

- LeGates, T. A., Fernandez, D. C., & Hattar, S. (2014). Light as a central modulator of circadian rhythms, sleep and affect. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 15(7), 443–454.

- Whelan, H. T., Smits, R. L., Buchman, E. V., et al. (2001). Effect of NASA light-emitting diode irradiation on wound healing. Journal of Clinical Laser Medicine & Surgery, 19(6), 305–314.

- Kamler, J. F. (2022). Cold exposure and heat stress: mechanisms of hormesis and dopamine modulation. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 16, 986541.

- Ludwig, D. S. (2002). The glycemic index: physiological mechanisms relating to obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. JAMA, 287(18), 2414–2423.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. Harper & Row.

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268.

- Salamone, J. D., & Correa, M. (2012). The mysterious motivational functions of mesolimbic dopamine. Neuron, 76(3), 470–485.

- Cools, R., Clark, L., & Robbins, T. W. (2004). Differential responses in human striatum and prefrontal cortex to changes in object and rule relevance. Journal of Neuroscience, 24(5), 1129–1135.

- Ericsson, K. A., Krampe, R. T., & Tesch-Römer, C. (1993). The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychological Review, 100(3), 363–406.

- Volkow, N. D., Wang, G. J., Newcorn, J., et al. (2007). Depressed dopamine activity in caudate and preliminary evidence of limbic involvement in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64(8), 932–940.

- Sagvolden, T., Johansen, E. B., Aase, H., & Russell, V. A. (2005). A dynamic developmental theory of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) predominantly hyperactive/impulsive and combined subtypes. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 28(3), 397–419.

- Glimcher, P. W. (2011). Understanding dopamine and reinforcement learning: the dopamine reward prediction error hypothesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(Suppl 3), 15647–15654.

Discussion