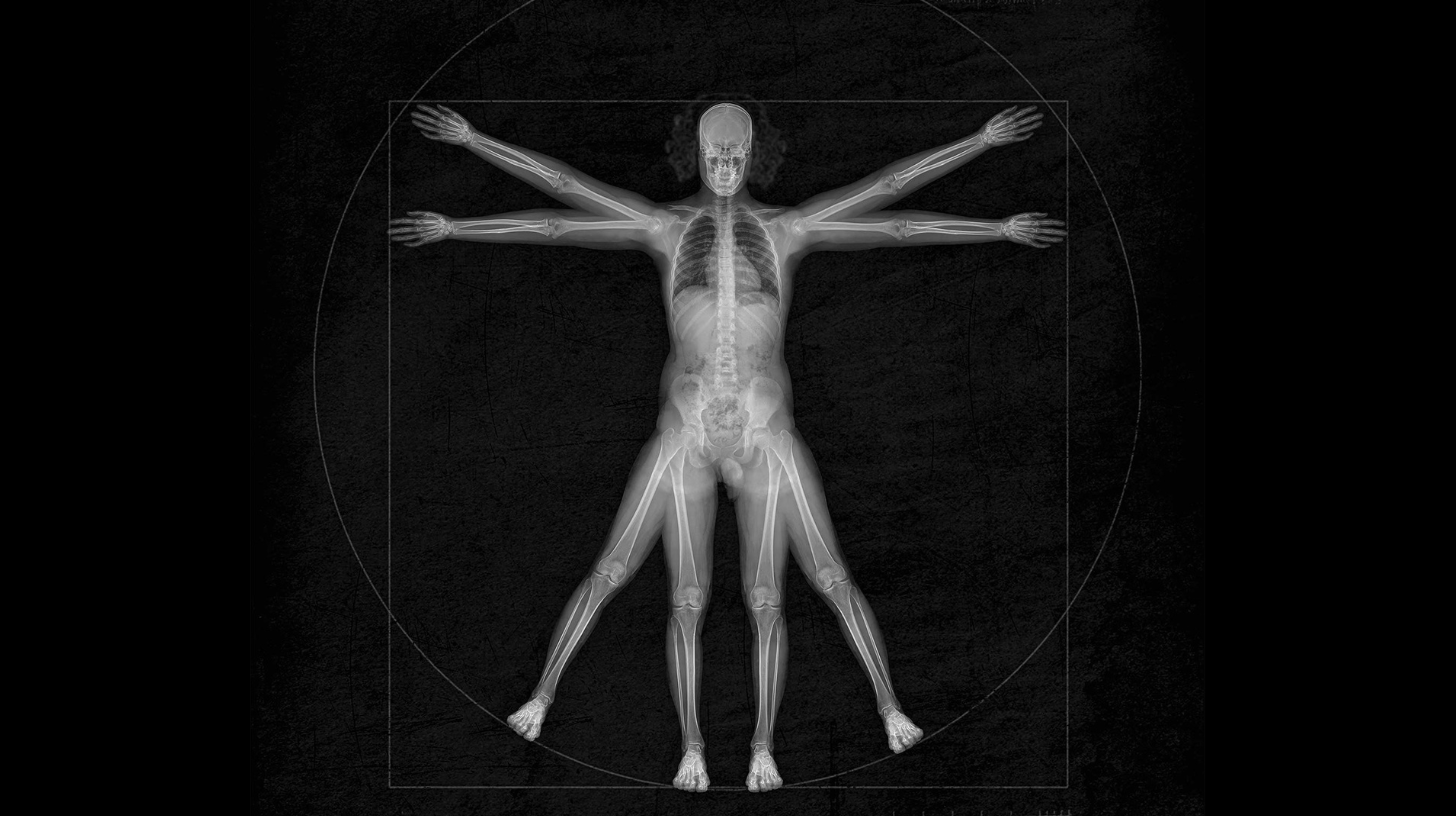

01 Anatomy of a DRIVEN Human

High performers aren’t chasing success—they’re chasing dopamine. Learn how genetic wiring fuels relentless drive, risk-taking, and innovation, and why structure is the key to unlocking their full potential.

Introduction

High performers aren’t chasing success—they’re chasing dopamine. Their drive isn’t a mindset; it’s a genetic compulsion. But without structure, this potential turns to chaos.

Entrepreneurship, as well as elite-level athletics and high-risk uniformed tactical operations, are their proving grounds. Dopamine is their fuel. High-performance living is the key to maximizing their biology.

What Makes Someone DRIVEN?

The DRIVEN brain operates differently. It’s wired for relentless pursuit, calculated risk, and infinite progress. At its core are two genetic markers:

DRD2 - The immediacy gene—high-stakes decisions, fast execution, hunger for quick wins¹

DRD4 - The explorer gene—long-term vision, future fixation, an obsession with “what’s next”²

Together, these genes create a dopamine-seeking machine, constantly scanning for bigger challenges, greater impact, and higher stakes.

The Dopamine Loop

Dopamine isn’t about pleasure—it’s about anticipation. The DRIVEN thrive on the pursuit more than the reward. It’s why they:

Build businesses, then immediately look for the next opportunity³

Train harder, only to set a new, more extreme goal⁴

Achieve success, but never feel “done”⁵

Their drive is biological, not voluntary. When harnessed, it creates innovation, dominance, and legacy. When mismanaged, it leads to burnout, self-destruction, and dissatisfaction.

The 10 Traits of DRIVEN Humans

Every DRIVEN individual exhibits predictable psychological traits—patterns shaped by their genetics, neurology, and environment.

- Obsession – Locks in deeply but can neglect other priorities⁶

- Big Picture Thinking – Sees macro-trends, not just tasks⁷

- Adaptive Identity – Becomes what the environment requires⁸

- Multi-Thinking – Processes multiple scenarios at once⁹

- Boredom Intolerance – Needs novelty, challenge, and momentum¹⁰

- Horizoning – Always scanning for what’s next¹¹

- Intuitive Sensing – Detects patterns, shifts, and unspoken cues¹²

- Risk-Taking – Prioritizes potential rewards over perceived risks¹³

- Perfectionism – Sets impossibly high standards¹⁴

- Grit – Fails fast, recovers faster¹⁵

The Hidden Cost of Being DRIVEN

Without structure and alignment, these traits can turn destructive. Disorder leads to burnout. Lack of purpose leads to chaos.

The DRIVEN who fail to channel their energy often experience:

- Restlessness – Perpetual dissatisfaction with current success¹⁶

- Impulsivity – Seeking stimulation at the expense of stability¹⁷

- Overcommitment – Juggling too many ventures, relationships, or ideas¹⁸

- Addiction – Using stimulants (work, substances, or adrenaline) to regulate dopamine¹⁹

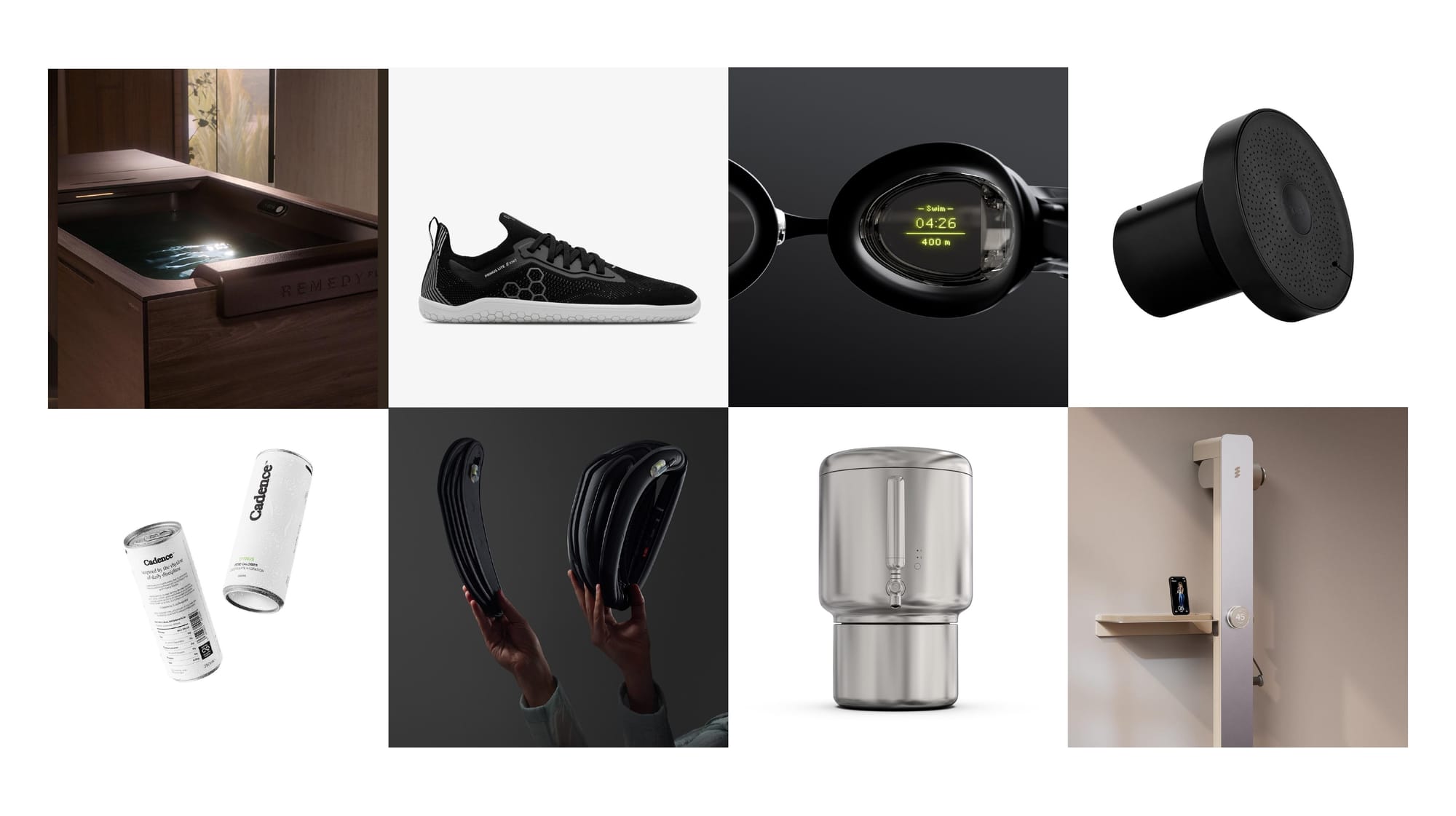

Harnessing Drive: The Power of High-Performance Living

High-performance living aligns biology with purpose. It ensures drive is sustainable, structured, and effective.

The solution is integration across four key domains:

- Body – Strength, endurance, neurochemical optimization²⁰

- Brain – Cognitive clarity, emotional regulation, strategic focus²¹

- Brand – Identity, authority, personal legacy²²

- Business – Scalable impact, wealth, innovation²³

When all four align, drive becomes a weapon—one that fuels creation, not destruction.

Conclusion

Being DRIVEN isn’t a mindset—it’s a biological reality.

The difference between top 2% success and burnout is structure, precision, and alignment.

Entrepreneurs aren’t in business for wealth or status. They’re in it for the dopamine.

When optimized, this creates legacy and impact. When neglected, it leads to chaos.

The choice isn’t whether to be DRIVEN. It’s whether to control it—or let it control you.

References

- Blum, K., et al. (1990). Association of the A1 allele of the D2 dopamine receptor gene with severe alcoholism. JAMA.

- Wang, E., et al. (2004). The genetic variation of DRD4 and novelty seeking in humans. Nature Neuroscience.

- Zald, D. H., et al. (2008). Midbrain dopamine receptor availability is inversely associated with novelty-seeking traits in humans. The Journal of Neuroscience.

- Cloninger, C. R. (1987). A systematic method for clinical description and classification of personality variants. Archives of General Psychiatry.

- Volkow, N. D., et al. (1999). Dopamine transporters decrease with age in healthy subjects. Journal of Neuroscience.

- Berridge, K. C., et al. (2003). Dopamine and reward: The anhedonia hypothesis 30 years on. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory.

- Hartmann, T. (1993). The Hunter vs. Farmer Hypothesis: An evolutionary perspective on ADHD. Psychological Bulletin.

- Gray, J. R., et al. (2002). Neural mechanisms of cognitive control and intelligence. Nature Reviews Neuroscience.

- Schilling, C., et al. (2012). Dopamine and entrepreneurial risk-taking: Genetic and neurobiological foundations. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience.

- Cohen, M. X., et al. (2005). Individual differences in extraversion and dopamine genetics predict neural reward responses. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience.

- Buckholtz, J. W., & Meyer-Lindenberg, A. (2012). MAOA and the neurogenetics of human aggressive behavior. Trends in Neurosciences.

- Bechara, A., et al. (1999). Decision-making deficits, linked to impaired activation of the amygdala, in individuals with high novelty-seeking behavior. Science.

- Robbins, T. W., et al. (2012). Dopamine, motivation, and reward. Nature Reviews Neuroscience.

- Peterson, J. B., et al. (2002). Dopaminergic functioning and achievement motivation in high-performance individuals. Personality and Individual Differences.

- Duckworth, A. L., et al. (2007). Grit: Perseverance and passion for long-term goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

- Kashdan, T. B., & Steger, M. F. (2007). Curiosity and pathways to well-being and meaning in life. Journal of Research in Personality.

- Sapolsky, R. M. (2004). Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers: The Science of Stress and Resilience. Holt Paperbacks.

- Hirsh, J. B., et al. (2009). Openness to experience and brain activity patterns in novel decision-making. Journal of Neuroscience.

- Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Four ways five factors are basic. Personality and Individual Differences.

- Kandel, E. R. (2001). The molecular biology of memory storage: A dialogue between genes and synapses. Science.

- Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. Random House.

- Voon, V., et al. (2010). Dopaminergic medication increases impulsivity in Parkinson’s disease. Neuropsychopharmacology.

- Montague, P. R., et al. (2006). A framework for mesencephalic dopamine systems based on predictive Hebbian learning. Journal of Neuroscience.

Discussion