06 Achieve Paragon Status

Top 2% performance is the result of engineered efficiency. A Paragon is rare: the 100-carat diamond, the gold standard of excellence. Learn how elite entrepreneurs leverage their biology through design and systems thinking to perform at a level most never reach.

Introduction

The term “elite” is overused. Paragon isn’t. A Paragon is the top 2%. The statistical outlier. The one who doesn’t just perform, but redefines what performance is. In a culture obsessed with hacks, trends, and comfort, Paragons pursue something different: constraint.

This article outlines the architecture of Top 2% performance through the lens of the DRIVEN. These individuals aren’t optimized by rest. They’re regulated by rhythm. And they don’t aim to do more—they aim to do what matters, precisely and relentlessly.

The Neurobiology of Elite Focus

Top 2% performers don’t have more willpower—they have better systems for reducing cognitive drag. The DRIVEN carry dopamine receptor variants (DRD2/DRD4) linked to low dopamine sensitivity and high novelty seeking¹. These traits, if unmanaged, lead to impulsivity and distraction. But when channeled through structure, they produce sustained intensity.

Paragons build rituals that offload executive burden. They operate in low-friction environments that eliminate nonessential choices, reduce context switching, and elevate deep work. Research shows that external structure improves attention and emotional regulation in individuals with ADHD-like dopaminergic traits². What looks like discipline is often systematized constraint.

This isn’t mindset. It’s neurochemical design.

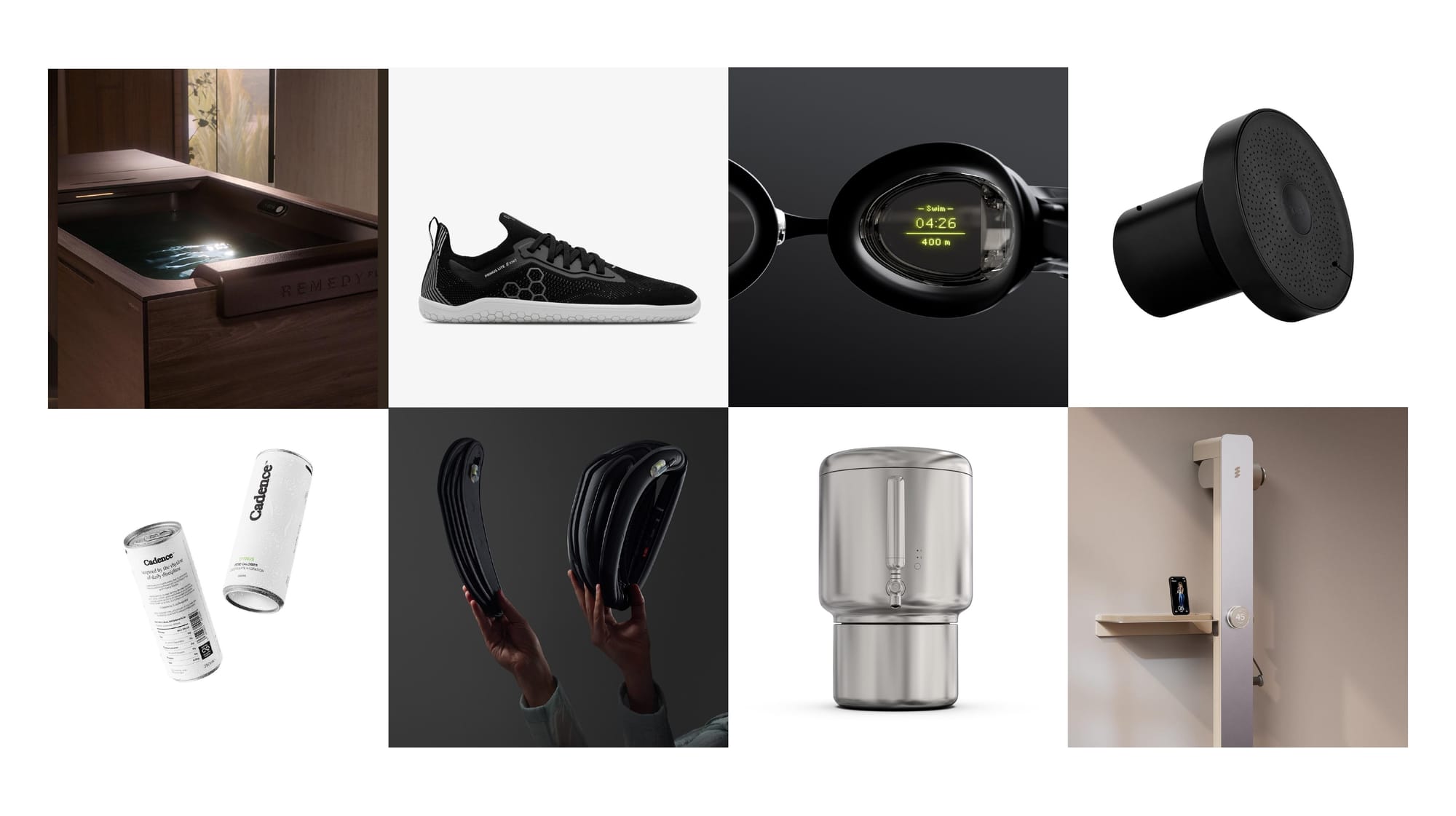

Designing the Paragon Environment

The brain was not built for high performance. It was built for survival. Paragons reverse-engineer their environment to serve precision, clarity, and speed.

Minimalism reduces decision fatigue. High-contrast visuals improve memory and attention³. Routine increases task completion and consistency⁴. Every variable is intentional: black-and-white workspaces, reduced inputs, tool standardization, and asynchronous workflows.

This environment is more than aesthetic. It’s an external nervous system. The Paragon doesn’t rely on motivation. They rely on infrastructure.

Systems Thinking as a Biological Advantage

Paragons think in systems. Not tasks. Not goals. Systems.

They design feedback loops, track leading indicators, and automate accountability. They understand that structure scales energy. According to self-determination theory, autonomy and competence are biologically reinforcing⁵. Systems that allow for visible progress and self-correction create internal reward, reducing the need for external validation.

Deliberate practice research confirms that top performers build layered, repeatable frameworks to sharpen skills over time⁶. Paragons are not reacting. They’re iterating.

Friction and Flywheels

Top 2% performance doesn’t emerge from ease—it’s the outcome of intelligent friction. For DRIVEN individuals with reduced dopamine sensitivity, challenge isn’t just a preference. It’s a requirement. Structured tension activates effort-based reward circuits, allowing focus and drive to be sustained over time⁷. Flywheels—systems that build momentum through repetition and alignment—are the infrastructure that turns pressure into power.

When Body, Brain, Brand, and Business flywheels are designed to compound on one another, they generate self-reinforcing loops of performance. But without friction—novelty, deadlines, calibrated difficulty—momentum stalls. DRIVEN individuals need structured resistance, not as punishment, but as precision leverage. It’s not about removing effort. It’s about engineering constraint.

Conclusion

Paragon status isn’t about hustle. It’s about structure. Top 2% performance is a byproduct of engineered constraint: dopaminergic awareness, calibrated friction, and systems that reward focus over frenzy.

This isn’t for everyone. But for the DRIVEN—those wired for pursuit and wired against moderation—it’s not optional. It’s the only path.

References

- Blum, K., Noble, E. P., Sheridan, P. J., et al. (1990). Association of the A1 allele of the D2 dopamine receptor gene with severe alcoholism. JAMA, 263(15), 2055–2060.

- Volkow, N. D., Wang, G. J., Newcorn, J., et al. (2007). Depressed dopamine activity in caudate and limbic structures in ADHD. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64(8), 932–940.

- Hall, R. H., & Hanna, P. (2004). The impact of web page text-background color combinations on readability, retention, aesthetics, and behavioral intention. Behavior & Information Technology, 23(3), 183–195.

- Lally, P., et al. (2010). How are habits formed: Modelling habit formation in the real world. European Journal of Social Psychology, 40(6), 998–1009.

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268.

- Ericsson, K. A., Krampe, R. T., & Tesch-Römer, C. (1993). The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychological Review, 100(3), 363–406.

- Salamone, J. D., & Correa, M. (2012). The mysterious motivational functions of mesolimbic dopamine. Neuron, 76(3), 470–485.

Discussion